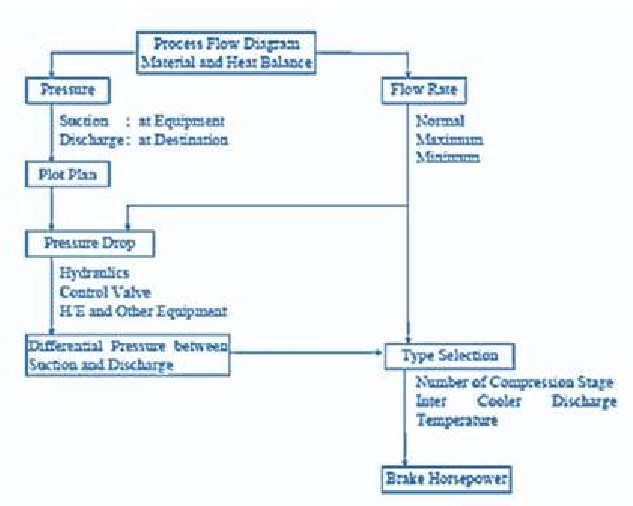

Compressor Selection Workflow : calculating and specifying gas

compressors

Follow us on Twitter ![]()

Question, remark ? Contact us at contact@myengineeringtools.com

| Section summary |

|---|

| 1. Introduction |

| 2. Main Concepts |

| 3. Calculation Methods and Formulas |

| 4. Calculation Examples |

1. Introduction

What is the purpose of this article on compressor selection?

Compressor selection is a critical task for process engineers, impacting both capital expenditure and long-term operational efficiency. This article outlines a structured workflow for selecting the appropriate compressor for a given application, emphasizing the key parameters and calculations required. Think of this as a guide to help you navigate the complexities of compressor selection.

1.1. Overview of Compressor Selection

What factors should be considered when selecting a compressor?

Selecting the right compressor demands a holistic evaluation, considering application-specific requirements, gas properties, operating conditions, and economic constraints. The goal is to identify the compressor type and configuration that delivers the required performance with optimal efficiency, reliability, and cost-effectiveness.

The initial step involves a thorough definition of the application. This includes specifying the gas composition, required inlet and outlet pressures, desired flow rate, and any specific process requirements. Following this, a detailed assessment of several key factors is necessary:

- Gas Properties: Accurate determination of the gas's molecular weight, specific heat ratio (n-value), critical pressure, critical temperature, and compressibility (Z) is crucial.

- Pressure and Temperature: Precise specification of inlet and outlet pressures and temperatures, including absolute and gauge values, is essential for correct calculations.

- Capacity Specifications: Understanding and converting between different capacity units such as ICFM, SCFM, and mass flow rates is necessary to ensure the selected compressor meets flow demands.

- Site Conditions: Altitude, ambient temperature range, and cooling water availability significantly impact compressor performance.

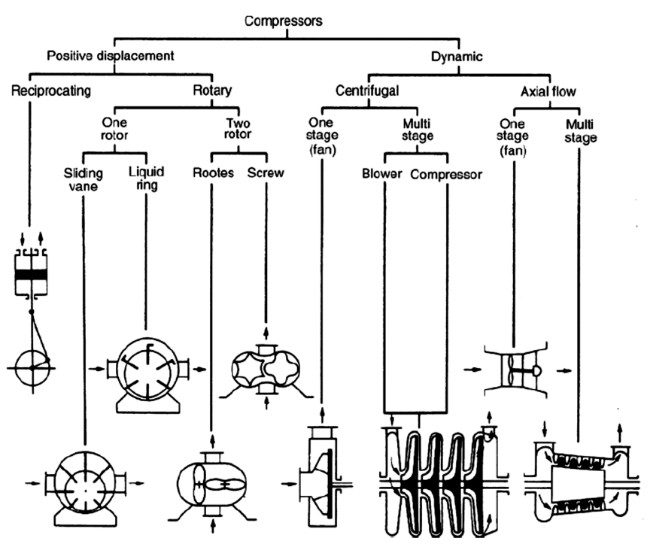

- Compressor Types: Evaluating the suitability of different compressor types (e.g., reciprocating, centrifugal, rotary screw, axial) and configurations (single-stage vs. multi-stage).

- Cost and Economic Factors: Balancing initial capital cost with long-term operating and maintenance costs, including energy consumption and potential downtime.

- Reliability and Availability: Selecting a compressor that meets the required reliability and availability standards for the application is essential for minimizing process disruptions.

- Scope of Supply: Defining the scope of supply, including the compressor package, driver (motor, turbine, etc.), control system, and auxiliary equipment.

The selection process often involves iterative calculations and comparisons of different compressor options to identify the compressor that best meets the specific needs of the application.

1.2. Importance of a Structured Workflow

Why is a structured workflow important for compressor selection?

Compressor selection is a complex process with significant implications for process efficiency and cost. A structured workflow is essential for ensuring a successful outcome. Without a systematic approach, critical parameters can be overlooked, leading to suboptimal compressor selection, increased operational costs, and potential safety hazards.

A well-defined workflow provides several key benefits:

- Comprehensive Evaluation: A structured approach ensures that all relevant factors, including gas properties, operating conditions, site constraints, and economic considerations, are systematically evaluated.

- Reduced Errors: By breaking down the selection process into discrete steps, a structured workflow minimizes the potential for errors in data collection, calculations, and decision-making.

- Optimized Performance: A systematic evaluation allows for a more accurate prediction of compressor performance, enabling the selection of a compressor that is optimally sized and configured for the specific application.

- Cost Control: A structured workflow helps to identify and evaluate all relevant cost factors, allowing for a more informed decision that balances performance requirements with economic constraints.

- Improved Communication: A well-defined workflow provides a clear framework for communication and collaboration between process engineers, equipment vendors, and other stakeholders.

- Enhanced Safety: By systematically evaluating potential safety hazards and implementing appropriate safeguards, a structured workflow helps to ensure the safe and reliable operation of the compressor system.

By following a structured workflow that includes defining the application, gathering detailed data, performing calculations, evaluating compressor types, and considering economic factors, process engineers can make informed decisions and select the compressor that best meets the needs of their specific application. Remember, shortcuts often lead to problems down the line.

2. Main Concepts

What are the fundamental concepts for effective compressor selection?

2.1. Defining Compressor Applications

What elements should be included in a complete compressor application definition?

The initial and arguably most crucial step in compressor selection is a precise and comprehensive definition of the application. This involves clearly articulating the purpose of the compressor within the overall process and meticulously documenting all relevant operating parameters. A complete application definition should include the following elements:

- Gas Composition: For gas mixtures, a detailed compositional analysis, specifying each component and its respective mole or weight fraction, is required. Variations in gas composition over time should also be documented.

- Inlet Conditions: Define the suction pressure (Ps) and suction temperature (Ts) at the compressor inlet, expressed in absolute units (psia or bara, °R or °K). Specify the expected range of variation for both pressure and temperature.

- Discharge Conditions: Specify the required discharge pressure (Pd) and discharge temperature (Td) at the compressor outlet, expressed in absolute units and including acceptable tolerances. Any limitations on the maximum allowable discharge temperature should be clearly stated.

- Capacity Requirements: Determine the required flow rate, considering both average and peak demands. Specify the flow rate units (e.g., SCFM, ICFM, lb/hr) and the reference conditions.

- Process Requirements: Identify any specific process constraints, such as the need for oil-free compression, discharge temperature limitations, pressure pulsation limits, or specific materials of construction.

- Site Conditions: Document the environmental conditions at the installation site, including altitude, ambient temperature range, cooling water availability, and any hazardous area classifications.

- Duty Cycle: Define the expected operating schedule of the compressor, including the number of hours per day, days per week, and any seasonal variations.

- Scope of Supply: Clearly define the scope of supply, including the compressor package, driver, control system, and any auxiliary equipment.

A clear and concise written statement summarizing the application is highly recommended. For example: "This compressor will compress a mixture of methane and ethane from a low-pressure storage tank to a high-pressure pipeline. The compressor must operate continuously, with a flow rate ranging from 1000 to 1200 SCFM and a discharge pressure of 1200 psig. Oil-free compression is required to prevent contamination of the gas stream." This kind of clarity will save you headaches later.

2.2. Key Parameters: Gas Properties (MW, n Value, Critical Values)

Why are gas properties important for compressor selection?

Accurate knowledge of the gas properties is important for proper compressor selection and performance prediction. These properties dictate the thermodynamic behavior of the gas during compression and directly influence the compressor's power requirements, discharge temperature, and overall efficiency. The key gas parameters to consider are:

- Molecular Weight (MW): The molecular weight of the gas or gas mixture. For gas mixtures, the molecular weight is calculated as the weighted average of the molecular weights of the individual components, based on their mole fractions: MWmix = Σ (xi * MWi).

- Specific Heat Ratio (n-value): Also known as the isentropic exponent or adiabatic index (k), this value represents the ratio of specific heat at constant pressure (Cp) to specific heat at constant volume (Cv). It is critical for calculating the adiabatic or polytropic head, discharge temperature, and power requirements.

- Critical Pressure (Pc) and Critical Temperature (Tc): These thermodynamic properties are essential for determining the compressibility factor (Z). They are used to calculate the reduced pressure (Pr = P/Pc) and reduced temperature (Tr = T/Tc).

- Compressibility Factor (Z): A dimensionless factor that corrects for the non-ideal behavior of real gases. For preliminary estimations, assuming Z = 1.0 may be acceptable. However, for accurate performance predictions, especially at high pressures, the compressibility factor must be determined using appropriate equations of state or generalized compressibility charts.

These gas properties can be obtained from published thermodynamic tables, online databases, or process simulation software. For gas mixtures, appropriate mixing rules must be used to calculate the average properties. Don't rely on rules of thumb when dealing with complex gas mixtures; accurate data is essential.

2.3. Pressure Considerations: Absolute vs. Gauge Pressure

What is the difference between gauge and absolute pressure, and why is it important?

Pressure is a fundamental parameter in compressor selection, and it is crucial to differentiate between gauge pressure and absolute pressure.

- Gauge Pressure (psig/barg): Pressure measured relative to the surrounding atmospheric pressure.

- Absolute Pressure (psia/bara): Pressure measured relative to a perfect vacuum. This is the total pressure exerted and is essential for all thermodynamic calculations.

The relationship between these two pressure measurements is defined by the following equations:

- psia = psig + Pamb

- bara = barg + Pamb

Where Pamb represents the local atmospheric or barometric pressure. All compressor calculations must be performed using absolute pressures. Atmospheric pressure varies with altitude, so the location of the compressor installation significantly impacts this conversion.

| Altitude above sea level (ft) | Atmospheric Pressure (psia) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 14.69 |

| 500 | 14.42 |

| 1,000 | 14.16 |

| 1,500 | 13.91 |

| 2,000 | 13.66 |

| 2,500 | 13.41 |

| 3,000 | 13.16 |

| 3,500 | 12.92 |

| 4,000 | 12.68 |

| 4,500 | 12.45 |

| 5,000 | 12.22 |

| 5,500 | 11.99 |

| 6,000 | 11.77 |

| 6,500 | 11.55 |

| 7,000 | 11.33 |

| 7,500 | 11.12 |

| 8,000 | 10.91 |

| 8,500 | 10.70 |

| 9,000 | 10.50 |

| 9,500 | 10.30 |

| 10,000 | 10.10 |

| 10,500 | 9.90 |

| 11,000 | 9.71 |

| 11,500 | 9.52 |

| 12,000 | 9.34 |

| 12,500 | 9.15 |

| 13,000 | 8.97 |

| 13,500 | 8.80 |

| 14,000 | 8.62 |

| 14,500 | 8.45 |

Table 3.1: Atmospheric Pressure vs. Altitude

Section 3.1 provides a table of atmospheric pressure versus altitude to facilitate accurate conversions. Remember to use the correct atmospheric pressure for your location.

2.4. Temperature Considerations: Absolute vs. Gauge Temperature

Why is it important to use absolute temperature in compressor calculations?

Similar to pressure, temperature must be expressed in absolute units for all compressor calculations, as thermodynamic relationships are based on absolute temperature scales.

- Gauge Temperature (°F/°C): Temperature measured relative to an arbitrary zero point.

- Absolute Temperature (°R/°K): Temperature measured relative to absolute zero.

The conversion formulas are:

- °R = °F + 460

- °K = °C + 273.15

Ensure that all temperature values used in calculations are converted to absolute units (°R or °K) and that units are consistent throughout the process. Consistency is key to avoiding errors.

2.5. Capacity Specifications: ICFM, SCFM, and Conversion

What is ICFM, and how do you convert between ICFM and SCFM?

Compressor capacity represents the volumetric flow rate of gas, but it is often specified using different units and reference conditions. For compressor selection, Inlet Cubic Feet per Minute (ICFM) is the most important parameter, as it represents the actual volume of gas the compressor ingests per minute at its inlet conditions (Ps, Ts). All other capacity specifications must be converted to ICFM to ensure accurate compressor sizing.

Common capacity specifications include:

- ICFM (Inlet Cubic Feet per Minute): The actual volumetric flow rate at the compressor inlet conditions.

- ACFM (Actual Cubic Feet per Minute): The actual volumetric flow rate at any specified set of conditions. If these conditions match the compressor inlet, ACFM equals ICFM.

- SCFM (Standard Cubic Feet per Minute): The volumetric flow rate corrected to "standard" reference conditions (e.g., 14.7 psia and 60°F).

- MSCFD (Thousand Standard Cubic Feet per Day): Similar to SCFM, but expressed on a daily basis.

- Mass Flow Rate (e.g., lb/hr, kg/hr): The mass of gas flowing per unit time.

The conversion formula from SCFM to ICFM is:

- ICFM = SCFM * (Pstd / Ps) * (Ts / Tstd) * (Zs / Zstd)

Where:

- Pstd and Tstd are the standard pressure and temperature.

- Ps and Ts are the compressor suction pressure and temperature (absolute units).

- Zs and Zstd are the compressibility factors at suction and standard conditions, respectively.

For preliminary calculations, the ratio Zs/Zstd can be assumed to be 1. Be aware of the specific standard conditions used for SCFM, as different standards exist. Always double-check the standard conditions used in any given specification.

3. Calculation Methods and Formulas

What calculation methods and formulas are essential for compressor selection?

3.1. Converting Gauge Pressure to Absolute Pressure

How do you convert gauge pressure to absolute pressure?

As discussed in Section 2.3, compressor calculations require absolute pressure values. The conversion from gauge pressure to absolute pressure is performed using the following formulas:

- PSIA = PSIG + Pamb

- bara = barg + Pamb

Where Pamb is the local barometric pressure. Use the data in Table 3.1 to determine Pamb based on site altitude. For critical applications, direct barometric pressure measurement is recommended.

3.2. Converting Temperature Scales

How do you convert between Fahrenheit and Rankine, and Celsius and Kelvin?

As discussed in Section 2.4, compressor calculations require absolute temperature values. The conversion from gauge temperature to absolute temperature is performed using the following formulas:

- °R = °F + 460

- °K = °C + 273.15 (Use 273 for most engineering calculations)

3.3. Calculating Inlet Cubic Feet per Minute (ICFM) from SCFM

How do you calculate ICFM from SCFM?

As established in Section 2.5, converting all capacity specifications to ICFM is crucial for accurate compressor selection. The conversion formula is:

- ICFM = SCFM * (Pstd / Ps) * (Ts / Tstd) * (Zs / Zstd)

Where:

- Pstd = Standard pressure (absolute). Common values are 14.696 psia or 14.7 psia.

- Ps = Compressor suction pressure (absolute).

- Ts = Compressor suction temperature (absolute) in °R.

- Tstd = Standard temperature (absolute). Common values are 519.67 °R or 520 °R (60°F).

- Zs = Compressibility factor at suction conditions.

- Zstd = Compressibility factor at standard conditions.

For preliminary calculations, assuming Zs = Zstd = 1 is often acceptable.

3.4. Calculating Polytropic or Adiabatic Head

How do you calculate polytropic and adiabatic head?

The polytropic or adiabatic head represents the amount of energy imparted to the gas by the compressor. The polytropic head calculation is generally preferred as it provides a more realistic representation of the actual compression process.

1. Polytropic Head (Hp):

- Hp = (Z1 * R * T1 / ((n-1)/n)) * (((P2 / P1)^((n-1)/n)) - 1)

2. Adiabatic Head (Hs):

- Hs = (Z1 * R * T1 / ((k-1)/k)) * (((P2 / P1)^((k-1)/k)) - 1)

Where:

- Z1 = Compressibility factor at the compressor inlet conditions

- R = Gas constant (1545 / MW)

- T1 = Compressor suction temperature (absolute)

- P1 = Compressor suction pressure (absolute)

- P2 = Compressor discharge pressure (absolute)

- n = Polytropic exponent

- k = Specific heat ratio (Cp/Cv)

The polytropic exponent (n) is related to the polytropic efficiency (ηp) and the specific heat ratio (k) by the fundamental relationship:

- (n-1)/n = (1/ηp) * (k-1)/k

Typical polytropic efficiencies range from 0.70 - 0.85 for centrifugal compressors and 0.75 - 0.90 for reciprocating compressors. Remember that these are typical values; actual efficiencies can vary.

3.5. Calculating Specific Speed (Ns)

How do you calculate specific speed, and what does it indicate about compressor type?

Specific speed (Ns) is a dimensionless parameter used to classify compressor impellers and helps in selecting the appropriate compressor type.

- Ns = N * sqrt(Q) / H^(3/4)

Where:

- N = Compressor speed (RPM)

- Q = Inlet flow rate (ICFM)

- H = Adiabatic head (ft-lbf/lbm)

Approximate ranges for different compressor types are:

- Radial (Centrifugal): Ns = 400 - 2500

- Mixed Flow: Ns = 2000 - 5000

- Axial: Ns = 4500 - 12000+

3.6. Estimating Number of Impellers/Stages

How do you estimate the number of stages required for a compressor?

The number of impellers or stages required for a compressor is directly related to the total head required and the achievable head per stage.

- Number of Stages = Total Head / Head per Stage

The Total Head is calculated using the polytropic or adiabatic head equations. The Head per Stage is dependent on compressor type, impeller design, and operating conditions. Typical head per stage values for centrifugal compressors range from 5,000 to 12,000 ft-lbf/lbm. Modern, high-performance impellers can achieve 15,000 ft-lbf/lbm or more. The number of stages is typically rounded up to the nearest whole number. Always consult with compressor vendors to confirm the achievable head per stage for your specific application.

3.7. Calculating Gas Horsepower

How do you calculate the gas horsepower required for a compressor?

Calculating the gas horsepower is a crucial step in sizing the compressor driver (e.g., electric motor) and estimating energy consumption. The correct formula for gas compression is based on the mass flow rate and the head developed by the compressor.

Gas HP = (mass flow [lb/min] * Head [ft-lbf/lbm]) / (33,000 * η_overall)

Where:

- mass flow = The mass of gas flowing through the

compressor per minute. It is calculated from the inlet volumetric

flow (ICFM) and the gas density at the inlet.

mass flow (lb/min) = ICFM * density_inlet (lb/ft³)

- Head = Polytropic or Adiabatic Head (ft-lbf/lbm), as calculated in Section 4.4.

- η_overall = Overall compressor efficiency (dimensionless). This accounts for mechanical and thermodynamic losses.

To determine the power required from the driver, divide the gas horsepower by the driver efficiency.

| Compressor Type | Typical Overall Efficiency, η |

|---|---|

| Centrifugal | 0.70 – 0.85 |

| High Speed Reciprocating | 0.72 – 0.85 |

| Low Speed Reciprocating | 0.75 – 0.90 |

| Rotary Screw | 0.65 – 0.75 |

Table 4.1: Typical Overall Compressor Efficiencies

4. Calculation Examples

What are some practical examples of compressor selection calculations?

This section provides practical examples demonstrating the application of the formulas and methods described in Section 3.

4.1. Example: Converting Pressure and Temperature

How do you convert pressure and temperature given altitude and gauge readings?

A compressor station located at an altitude of 2,000 ft above sea level draws in ambient air. The gauge pressure at the compressor inlet is measured as 2.5 psig, and the temperature is 86°F. Determine the absolute pressure (psia) and absolute temperature (°R) at the compressor inlet.

- Determine atmospheric pressure: From Table 3.1, the atmospheric pressure at 2,000 ft is approximately 13.66 psia.

- Convert gauge pressure to absolute pressure:

- PSIA = PSIG + Pamb = 2.5 psig + 13.66 psia = 16.16 psia

- Convert temperature from Fahrenheit to Rankine:

- °R = °F + 460 = 86°F + 460 = 546 °R

The absolute pressure is 16.16 psia, and the absolute temperature is 546 °R.

4.2. Example: Calculating ICFM for Nitrogen Compression

How do you calculate ICFM for nitrogen compression given SCFM and operating conditions?

A nitrogen compressor is required to handle 250 SCFM. The compressor suction pressure is 25 psia, and the suction temperature is 100°F. Calculate the ICFM. Assume standard conditions are 14.7 psia and 60°F, and the compressibility factor ratio Zs/Zstd = 1.

- Convert temperature from Fahrenheit to Rankine:

- °R = °F + 460 = 100°F + 460 = 560 °R

- Apply the ICFM conversion formula:

- ICFM = SCFM * (Pstd / Ps) * (Ts / Tstd) * (Zs / Zstd)

- ICFM = 250 SCFM * (14.7 psia / 25 psia) * (560 °R / 520 °R) * 1

- ICFM = 158.5 CFM

The ICFM for the nitrogen compressor is 158.5 CFM.

4.3. Example: Calculating Polytropic or Adiabatic Head for Nitrogen Compression

How do you calculate polytropic and adiabatic head for nitrogen compression?

A nitrogen compressor compresses nitrogen from 20 psia and 80°F to 150 psia. Assume Z1 = 1, R = 55.15 ft-lbf/lbm-°R, k = 1.4, and ηp = 0.8. Calculate the polytropic and adiabatic head.

- Convert temperature from Fahrenheit to Rankine:

- °R = °F + 460 = 80°F + 460 = 540 °R

- Calculate the polytropic exponent term ((n-1)/n):

- (n-1)/n = (1/ηp) * (k-1)/k = (1/0.8) * (1.4-1)/1.4 = 1.25 * 0.2857 = 0.3571

- Solving for n gives n = 1.555.

- Calculate the polytropic head (Hp):

- Hp = (Z1 * R * T1 / ((n-1)/n)) * (((P2 / P1)^((n-1)/n)) - 1)

- Hp = (1 * 55.15 * 540 / 0.3571) * (((150 / 20)^0.3571) - 1)

- Hp = 83,346 * (2.065 - 1) = 88,763 ft-lbf/lbm

- Calculate the adiabatic head (Hs):

- Hs = (Z1 * R * T1 / ((k-1)/k)) * (((P2 / P1)^((k-1)/k)) - 1)

- Hs = (1 * 55.15 * 540 / ((1.4-1)/1.4)) * (((150 / 20)^((1.4-1)/1.4)) - 1)

- Hs = 104,240 * (1.779 - 1) = 81,203 ft-lbf/lbm

The polytropic head is 88,763 ft-lbf/lbm, and the adiabatic head is 81,203 ft-lbf/lbm.

4.4. Example: Calculating Specific Speed (Ns) for Centrifugal Compressor Selection

How do you calculate specific speed and determine if a centrifugal compressor is suitable?

A centrifugal compressor is being considered for an application with the following parameters: Compressor speed (N) = 11,900 RPM, Inlet flow rate (Q) = 3,000 ICFM, and Adiabatic head (H) = 15,000 ft-lbf/lbm. Calculate the specific speed (Ns) and assess the suitability of a centrifugal compressor for this application.

- Apply the specific speed formula:

- Ns = N * sqrt(Q) / H^(3/4)

- Ns = 11,900 RPM * sqrt(3,000 CFM) / (15,000 ft-lbf/lbm)^(3/4)

- Ns = 11,900 * 54.77 / 1414.21 = 460.8

- Interpret the result:

- The calculated specific speed (Ns) is approximately 461. This value falls squarely in the range for a radial (centrifugal) compressor (400 - 2500). This calculation indicates that a centrifugal compressor is a suitable choice for this application, whereas an axial machine would be inefficient.

4.5. Example: Estimating Number of Impellers/Stages for a Centrifugal Compressor

How do you estimate the number of stages for a centrifugal compressor?

A centrifugal compressor is being designed to compress a gas with a total polytropic head requirement of 75,000 ft-lbf/lbm. Based on preliminary design considerations, a head per stage of 15,000 ft-lbf/lbm is deemed achievable. Estimate the number of stages required.

- Apply the number of stages formula:

- Number of Stages = Total Head / Head per Stage

- Number of Stages = 75,000 ft-lbf/lbm / 15,000 ft-lbf/lbm = 5

Approximately 5 stages are required. If the calculation yielded a non-integer result (e.g., 5.2), the number of stages would be rounded up to the next whole number (6 stages). Always consult with compressor vendors to confirm the achievable head per stage for your specific application.

4.6. Example: Comparative Power Calculation for Centrifugal vs. Reciprocating Compressor

How do you compare the power requirements of centrifugal and reciprocating compressors?

A compressor is required to handle 500 ICFM of nitrogen (MW=28, k=1.4) from 20 psia and 80°F to 150 psia. Compare the gas horsepower requirements of a centrifugal compressor (η=0.75) and a low-speed reciprocating compressor (η=0.90).

- Calculate Adiabatic Head (Hs): From Example 5.3, the adiabatic head for these conditions is 81,203 ft-lbf/lbm.

- Calculate Mass Flow Rate:

- T1 = 80°F + 460 = 540 °R

- Density = (P1 * 144 * MW) / (1545 * T1) = (20 * 144 * 28) / (1545 * 540) = 0.0965 lb/ft³

- Mass Flow = Q * Density = 500 ft³/min * 0.0965 lb/ft³ = 48.25 lb/min

- Calculate power for the centrifugal compressor:

- Gas HP = (mass flow * Head) / (33,000 * η)

- Gas HP = (48.25 lb/min * 81,203 ft-lbf/lbm) / (33,000 * 0.75) = 158.3 HP

- Calculate power for the reciprocating compressor:

- Gas HP = (48.25 lb/min * 81,203 ft-lbf/lbm) / (33,000 * 0.90) = 131.9 HP

4.7 Worked example — instrument air for a new chemical plant (completed)

Problem

statement (restated)

Supply instrument air meeting ISO

8573-1:2010 Class 1.2.1 to pneumatic actuators and

control valves. Design basis (given):

-

Current demand = 110 SCFM, add 20% future allowance → design SCFM = 110 × 1.20 = 132 SCFM (this is standard-condition flow).

-

Required discharge pressure = 100 psig.

-

Site = sea level, ambient = 70 °F.

-

Duty = continuous 24/7.

-

Assume air is “dry” at intake for conversion (no humidity correction) and compressibility Z ≈ 1 (low pressure, ambient conditions).

What we will deliver:

-

Convert SCFM → ICFM (inlet/actual conditions)

-

Compute inlet density & mass flow (lb/min, kg/s)

-

Compression ratio and thermodynamic heads (adiabatic & polytropic)

-

Estimate shaft / motor power and pick a conservative motor size

-

Recommend compressor type, air treatment (to meet ISO 8573-1:1.2.1), receiver and redundancy strategy

Step 1) Quick notes about air quality requirement (ISO 8573-1:2010 [1:2:1])

-

ISO 8573-1 class notation

[A:B:C]= Particles : Water : Oil. Class 1.2.1 = particulate class 1, water class 2 (pressure dew point per ISO table) and oil class 1 (very low oil). Practical implication: very low oil (≤0.01 mg/m³) and a pressure dew point ~ −40 °C (class 2 water), plus the tight particle counts of class 1. See manufacturer/standards summaries for the class table.

Step 2) Convert SCFM → ICFM (actual inlet CFM at inlet conditions)

Formula used (standard conversion, neglecting humidity for this worked example):

ICFM=SCFM×PactPstd×TstdTact×ZstdZact(we take Zact=Zstd=1 and Pstd=Pact at sea level so the pressure ratio is 1). See references for the SCFM→ACFM/ICFM method.

Numbers / assumptions

-

SCFM (design) = 132 SCFM (110 × 1.20) — SCFM referenced to standard 14.696 psia, 60 °F.

-

Standard T: 60 °F → 519.67 °R (°R = °F + 459.67).

-

Ambient suction T: 70 °F → 529.67 °R.

-

Ambient suction absolute pressure: 14.696 psia (sea level).

Compute:

ICFM=132×14.69614.696×519.67529.67=132×519.67529.67Numeric result (rounded reasonably):

ICFM=134.54 ft3/min (actual inlet conditions)(That 134.54 CFM is what the compressor must ingest at its inlet.)

Step 3) Inlet density and mass flow (consistent units used in the rest of the article)

We use the ideal-gas relation in US engineering units:

ρ=Rair×TactPact×144where:

-

Pact=14.696 psia, multiply by 144 to get lbf/ft²,

-

Rair=MWairRu with Ru≈1545.349 ft.lbf/(lb.mol.°R) and MWair≈28.9647 lb/lb.mol → Rair≈53.353 ft.lbf/(lb.°R). (This is standard).

Numeric:

-

Tact=70+459.67=529.67 °R.

-

ρ=53.353×529.6714.696×144=0.074886 lb/ft3.

Mass flow:

m˙=ρ×ICFM=0.074886 ft3lb×134.540 minft3=10.075 lb/min.Also:

m˙=10.075 lb/min≈0.07617 kg/s(≈604.5 lb/h)(KEpt several sig-figs for internal use; report final rounded values in text.)

Step 4) Compression ratio, adiabatic & polytropic head (ft-lb/lb) — thermodynamic sizing

Given: suction P1 = 14.696 psia, discharge P2 = 100 psig + 14.696 = 114.696 psia → compression ratio P2/P1=114.696/14.696=7.803.

Adiabatic (isentropic) specific head (ft-lb per lb of gas):

Hs=(kk−1)ZRT1[(P1P2)kk−1−1]Numeric result:

Hs≈78,997 ft.lbf/lbPolytropic head (accounts for non-ideal, finite polytropic efficiency)

If you want a more realistic “actual” compression work use the polytropic exponent n. With a polytropic efficiency assumption ηp=0.85 (reasonable for modern packaged rotary machines) the relationship

nn−1=ηp1⋅kk−1gives n≈1.5063. Then

Hp=(nn−1)RT1[(P1P2)nn−1−1]Numeric result:

Hp≈83,654 ft.lbf/lb(As expected, Hp > Hs when ηp<1.)

Step 5) Gas horsepower → driver sizing

Use standard conversion:

Gas HP=33,000×ηoverallm˙ [lb/min]×H [ft.lb/lb]where ηoverall = mechanical + thermodynamic + leakage combined (pick 0.75 as a reasonable packaged-compressor overall value for preliminary sizing).

Numeric (using polytropic head for a realistic estimate):

-

m˙=10.075 lb/min

-

Hp=83,654 ft.lbf/lb

-

ηoverall=0.75

Convert to motor requirement:

-

If motor efficiency ≈ 95% (0.95), required motor shaft HP ≈ 34.05/0.95=35.85 HP.

-

Allow routine design/service margin (service factor, motor selection) — common practice: 1.15 service factor (or pick next standard motor frame). Multiply: 35.85×1.15=41.2 HP.

Recommendation: specify ~40 HP to 50 HP motor depending on vendor package and preferred margin (practical choice: 40 HP packaged oil-free rotary screw often selected for this load, but because service factor result was 41.2 HP you may choose 50 HP for extra margin or confirm with vendor curves). Always finalize with vendor performance curves. (I chose conservative margins above — vendor will confirm precise package.)

Converted electrical power (rough):

electrical kW at design≈41.2 HP×0.746≈30.8 kW (full design+SF)Step 6) Equipment & air treatment recommendations to meet ISO 8573-1:2010 [1:2:1]

Compressor type

-

Best practice for ISO 1.2.1 (instrument air): oil-free compression (oil-free rotary screw, oil-free scroll) or oil-injected compressor with a robust multi-stage filtration & desiccant system. Many end-users prefer oil-free rotary screw packages for instrument air because they avoid the risk of oil breakthrough and reduce downstream filtration complexity. Vendor literature and whitepapers discuss the trade-offs (oil-free vs technically oil-free + filtration).

Drying

-

Class 2 water (≈ −40 °C pressure dew point) requires a desiccant (adsorption) dryer — refrigerated dryers typically only give ~ +3 °C dew point, so they are NOT adequate for −40 °C requirement. Regenerative/desiccant dryers can achieve −40 °C PDP (and lower).

Filtration / oil removal

-

To achieve oil ≤0.01 mg/m³ (ISO oil class 1) you need either: (a) an oil-free compressor, or (b) an oil-injected compressor + high-efficiency coalescing filters + activated carbon/adsorbers and monitoring. Many suppliers recommend oil-free machines for critical instrument air to avoid potential long-term vapour breakthrough.

Typical package layout (recommended):

-

Inlet filter → oil-free rotary screw compressor (VSD optional) → aftercooler → separator → coalescing pre-filter → desiccant dryer (regenerative) sized for 134 ACFM) → post-filter (particle/activated carbon as required) → receiver (sized below) → distribution. Add dew-point monitor and oil monitor downstream for verification.

Step 7) Receiver sizing & redundancy (practical notes)

Receiver volume (rule-of-thumb): industry rules vary. A common guidance is 3–5 gallons per CFM for system stability; some designers use 5–10 gal/CFM for larger systems or where buffer/peak shaving is required. For instrument air at 134 ICFM:

-

At 3 gal/CFM → 403 gal (~1,524 L)

-

At 5 gal/CFM → 672 gal (~2,540 L)

Pick toward the lower or higher end depending on expected short transients and compressor control strategy. For critical instrument air, also design N+1 redundancy (i.e., two compressors where any one can carry the load, or two compressors sized with duty/standby) — typical best practice for continuous 24/7 critical air.

Step 8) Control & efficiency considerations

-

Consider VSD (variable speed drive) compressors if load varies; VSD saves energy under partial load. For steady 24/7 critical instrument air with fairly constant demand, fixed speed + unloader control can be acceptable — check plant load profile. Vendor performance curves will show energy/cost tradeoffs.

-

Include pressure drop in inlet piping and filters (ICFM must be delivered after inlet losses). Specify inlet pressure to vendor (include allowance for inlet losses).

-

Include monitoring: dew-point sensor and oil-in-air monitor at point-of-use for verification of ISO class.

Step 10) Design checklist

-

Obtain vendor performance curves for candidate compressor packages (plot motive HP vs suction P / load curves) and revise motor sizing. (Vendor curves MUST be used to finalize).

-

Size desiccant dryer and filters to actual ACFM with manufacturer’s heat-load tables (desiccant dryers have published ∆T and heat duty curves).

-

Specify receiver volume (final value based on control philosophy and transient analysis).

-

Specify instrumentation: dew-point transmitter, oil monitor, flow-meter, pressure transducers.

-

Specify N+1 redundancy plan and surge/protection for downstream critical loads.

FAQ: Compressor Selection for Process Applications

1. What factors are critical in compressor selection?

Key factors include gas composition, inlet/outlet pressures, flow rate, site conditions (altitude, temperature), compressor type, reliability, and economic considerations like capital and operating costs.

2. Why is a structured workflow important for compressor selection?

A structured workflow ensures comprehensive evaluation, reduces errors, optimizes performance, controls costs, improves communication, and enhances safety by systematically addressing all critical factors.

3. What gas properties are essential for compressor selection?

Essential gas properties include molecular weight (MW), specific heat ratio (\( k \)), critical pressure (\( P_c \)), critical temperature (\( T_c \)), and compressibility factor (\( Z \)).

4. How do you convert gauge pressure to absolute pressure?

Absolute pressure (\( P_{\text{abs}} \)) is calculated as: \[ P_{\text{abs}} = P_{\text{gauge}} + P_{\text{ambient}} \] Where \( P_{\text{ambient}} \) is the local atmospheric pressure.

5. What is the difference between ICFM and SCFM?

ICFM (Inlet Cubic Feet per Minute) is the actual volumetric flow at the compressor inlet conditions. SCFM (Standard Cubic Feet per Minute) is flow corrected to standard conditions (e.g., 14.7 psia, 60°F). Conversion: \[ \text{ICFM} = \text{SCFM} \times \frac{P_{\text{std}}}{P_{\text{inlet}}} \times \frac{T_{\text{inlet}}}{T_{\text{std}}} \times \frac{Z_{\text{inlet}}}{Z_{\text{std}}} \]

6. How is polytropic head calculated?

Polytropic head (\( H_p \)) is calculated as: \[ H_p = \frac{Z \cdot R \cdot T_1}{\frac{n-1}{n}} \left[ \left( \frac{P_2}{P_1} \right)^{\frac{n-1}{n}} - 1 \right] \] Where \( n \) is the polytropic exponent, derived from polytropic efficiency (\( \eta_p \)) and specific heat ratio (\( k \)).

7. What is specific speed (\( N_s \)), and why is it important?

Specific speed (\( N_s \)) is a dimensionless parameter used to classify compressor types: \[ N_s = \frac{N \cdot \sqrt{Q}}{H^{3/4}} \] It helps in selecting the appropriate compressor type (e.g., centrifugal, axial).

8. How do you estimate the number of stages in a compressor?

The number of stages is estimated as: \[ \text{Number of Stages} = \frac{\text{Total Head}}{\text{Head per Stage}} \] Head per stage depends on compressor type and design.

9. How is gas horsepower calculated?

Gas horsepower is calculated as: \[ \text{Gas HP} = \frac{\dot{m} \cdot H}{33,000 \cdot \eta_{\text{overall}}} \] Where \( \dot{m} \) is mass flow rate, \( H \) is head, and \( \eta_{\text{overall}} \) is overall efficiency.

10. What are typical overall efficiencies for different compressor types?

Typical overall efficiencies are: - Centrifugal: 70–85% - High-speed reciprocating: 72–85% - Low-speed reciprocating: 75–90% - Rotary screw: 65–75%.

- https://www.psgdover.com/docs/default-source/blackmer-docs/training-materials/cb207.pdf?sfvrsn=b86a1445_5

- https://www.jmcampbell.com/tip-of-the-month/2015/07/how-to-estimate-compressor-efficiency/

- http://docs.codecalculation.com/thermodynamics/chap06.html

- https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1508&context=icec/1000

- https://jensapardi.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/centrifugal_compressor_manual1.pdf

- https://www.etivc.org/techpage_files/pump%20tutorial.pdf

- https://intech-gmbh.ru/en/compr_calculation_and_selection-2/